When I stepped aboard the C&C 52 for the first time, it was three days before the start of the 2000 Newport Bermuda Race. I had never done the race before and - almost on a whim - I had asked some friends in Newport if they knew of anyone looking for crew. This was just about a week before the start. One friend had heard about such an opportunity, but told me that he really didn’t know much about the boat or the skipper. I talked to the owner. He seemed knowledgeable and experienced and I was assured the boat was in excellent condition, having just crossed the Atlantic in the ARC where it had placed second.

Standing in the cockpit, I surveyed the scene. It was an older IOR design, a veritable winch farm. The hardware was big and beefy, and there was a rigger on board who was replacing the running backs. So far so good. I introduced myself to the owner, who enthusiastically welcomed me and offered to give me a tour of the vessel. There were two paid hands - able-bodied seaman types. One was a brooding Turk, the other a gregarious rastafarian from St Lucia who was fond of “smoking his chalice” every time the skipper was not around. The pair had done the ARC together with the owner and somehow had managed to get along well-enough despite being complete opposites.

Neither of the pedestal-driven primaries was fully functional, so while some of the crew offloaded all of the excess crap on the boat (including a 200 pound, ancient 3oz chicken chute that was soaking wet, stained and “well-ventilated” with holes), a couple of the offshore veterans and I tore down the winches. Eventually, we got one to function fairly well, but the other one would not shift gears and was balky, so we improvised a way to cleat off the old sheet so we could take in the new sheet on the one good winch.

Friday morning was the first time we left the dock. The owner had just gotten his new main - a heavy dacron style - so we went out early to bend it on and then get a little practice time in. We encountered some difficulties with the battens not fitting correctly, but were able to alter them so they’d work for the race. Sorting all of this out took a lot more time than we had, and by the time we got the main up, we were already in our starting sequence. We had not even had a practice tack, and now we were racing simply to get to the starting line with just the main up. The jib was hoisted around the one minute gun or so. We were on the windward end of the line - about 100 yards west of the committee boat, on the course side and still racing just to get to the proper side of the line. I was calling the start and saw an opening in the parade of starboard tackers at the boat-end and called for a jibe on the layline (as best as I could guess on a boat I had never sailed on) to the boat-end. As I always say “I’d rather be lucky than good!” and our timing was perfect; we hit the line at speed and won the entire start. (My stock with the owner jumped up quite a bit and I suddenly found myself as a watch captain!)

Seconds later, however, we heard a loud crunch. The big Swan behind us had tried to come down and make it inside the line but instead had dropped her bow into our transom, taking out a fist-sized chunk of fiberglass right at the edge of the transom. It was a fairly forceful collision. The Turk scrambled down below and somehow managed to patch the hull from the inside. It wasn’t completely water tight, but at least the ingress was slowed to a trickle.

To quote Gilligan’s Island “the weather started getting rough, the tiny ship got tossed” and 8 hours into the race more than half of the crew was completely disabled by seasickness. The fact that both heads had already blown up might have been a contributing factor. The stove had also decided to pack it in. For the next 36 hours, the five men who were still capable of sailing kept the boat moving. As we approached the Gulf Stream, the wind built up even more and we were beginning to endure the biggest waves I had ever seen. (Remember, this was my first real offshore race. The biggest waves I had seen to date were 10-footers in Block Island Sound. These were easily twice as big.) At one point during the night we fell off a wave so hard that one of the new running backstays parted in what sounded like a rifle shot. We scrambled to jerry-rig a replacement with the staysail halyard.

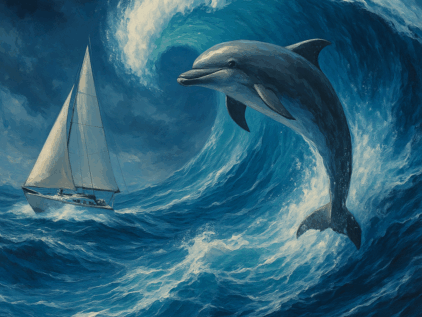

As dawn approached the waves were becoming truly monstrous - 25 feet. The boat would roll into a trough and the waves were literally over the spreaders. Out of the corner of my eye I saw a shadow in the waves. Then another. And another. Four or five of them. What the hell are they?! Suddenly, I saw a nose poke out of the wave above the spreaders. It was a dolphin. He stared down at us from about a three-story height. I swear he smiled at us crazy “hoo-mans". Then he dove down back into the wave and under the boat. He and a few other of the braver dolphins kept circling back through the waves, peeking down at us as the crests broke just off our beam. It was incredibly exhilarating. A real life experience.

Despite many of the challenges that we continued to face for the duration of the race (equipment breakdowns, crew clashes, lack of a stove, no working head, etc.), I can honestly say that those dolphins were the thing that made me fall in love with ocean racing in general, and the Newport Bermuda Race in particular.

Eight years later, my wife and I campaigned our Frers 45 Crazy Horse (formerly Brigadoon VI) in the 2008 NBR. Having sailed in 2000 on a boat that was thoroughly unprepared, I took those lessons to heart. We spent more than 18 months preparing, practicing, selecting crew, and upgrading our systems and sails, and managed a Second in class in 2008. That race also had many great stories and moments. Now that I have done 7 NBR’s and one Marion-Bermuda, I can tell you that every Bermuda race I’ve done has generated incredibly strong relationships, lots of funny stories, and we’ve even come away with our fair share of hardware.

While the 2000 edition was not one of my favorite Bermuda races, you never forget your first. And while I have looked down and seen dolphins many times, I’ve never again had another chance to look UP at them. That’s OK with me.

What advice would you give to someone considering their first Bermuda Race in 2026?

Start prepping now. I firmly believe that preparation plays a much bigger role in successfully completing - let alone competing in - this race. Every detail is important. One cotter pin can kill the dream.

In 2026, the Bermuda Race Foundation will celebrate not just 120 years of the Newport Bermuda Race, but also the 100th anniversary of the remarkable partnership between the Cruising Club of America and the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club. To honor this milestone of adventure, camaraderie, and seamanship, we’re inviting sailors to share their most memorable moments from past races in a special storytelling series called “This One Time in the Gulf Stream.” Whether it was a thrilling midnight spinnaker run, a tricky navigation call, a crew moment that kept spirits high, or even the lessons learned in tough conditions, we want to hear your stories — and see your photos — that capture the essence of what makes this race unforgettable. Learn more at https://bermudarace.com/this-one-time-in-the-gulf-stream/