Looking Back: 46th Thrash (2008), Runnerup Again

With the 50th Bermuda Race coming up in 2016,we're gathering stories of past races. Here, JOHN ROUSMANIERE remembers 2008 in Selkie. Submit your memories to: [email protected].

Some things are too special to do all the time, which I suppose is why I’ve sailed only eight Newport Bermuda Races since my first one in 1966. It has been my good fortune to be in three prize winners. Two of them were second-place boats that also were family boats owned by longtime friends. In "the reaching race" in 1980, we in Dave Noyes’ 37-foot yawl Elixir were runner-up to Rich Wilson’s Holger Danske. In 2008 I was a watch captain for Sheila McCurdy in her family’s 38-foot sloop Selkie, and after four days plus a few hours of very wet beating more than 650 miles from Newport to St. David’s Head, we ended up with only one of the 196 other boats ahead of us in the St. David's Lighthouse Division corrected standings, Peter Rebovich’s Cal 40 Sinn Fein.

Over all the time that I have occasionally raced to Bermuda, many of my peers have sailed in twice that number of races, but have never been invited to the prize ceremony at Government House, with its spectacular hilltop view of the archipelago of coral and cedar and small white houses. But I am lucky not only in the silverware department. As everybody knows (or at least should know) trophy-collecting is just one tick on the list of life’s satisfactions, and so is racing cutting-edge boats. Young professional crews and cant-keelers may race in the Bermuda Race, but this race is mostly about amateur sailors in normal good boats, some of them (both sailors and boats) with a few decades on them.

In these two races and a few others, I was shipmates with lifelong friends and very good sailors from my sailing home, which is Cold Spring Harbor, on Long Island, New York. My first offshore watch captain, in 1966 in another boat with Dave Noyes, was Jim McCurdy. He lived near our little yacht club—an institution so unfocused on high-performance sailing that it was (and still is) called a "beach club" and had (and still has) two tennis balls on its burgee. Jim taught me something, quietly encouraged me in his Scots way, and made me laugh a lot. For instance, when asked, “When are boats most likely to get into trouble?”, he replied, “At 2 o’clock in the morning.”

Later, this good man who did much to advance good boats and safe sailing was elected Commodore of the Cruising Club of America, one of the Bermuda Race’s two organizers (with the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club). There he worked to open the club’s doors to the many highly qualified women who went cruising and racing. One was his younger daughter, who in 2010 would be elected the CCA's first woman commodore. That lay in the future in June 2008. Here I was in a boat my old watch captain designed, with his daughter as skipper and his grandson on my watch—and we nearly won the race. Here is a brief look at how we did it.

First comes the boat. Jim, a gifted naval architect at McCurdy & Rhodes, built Selkie for himself in 1986 to be about the minimum size to qualify for the Bermuda Race. But here is one fine Bermuda Race and offshore boat. She has the easiest motion of any smaller boat I’ve sailed. In the very confused seas that we had through most of this race, down below she felt like a 50-foot cruiser, When the sheets and traveler are properly (meaning constantly) attended to, and the helmsman masters the fine art of small twitches (not great sweeps) with the wheel, she finds her way rapidly, and close to the wind.

A boat like that is a powerful weapon in a typical Bermuda Race, when you spend days with the wind ahead and the waters deeply ruffled, and you’re constantly searching for paths to the favorable sides of eddies spinning off the Gulf Stream. When I wrote my history of the race, A Berth to Bermuda, in 2006, one theme wove its way through the narrative: anyone who wishes to win the oldest of all ocean races must be prepared to be bold in choosing strategy and tactics. Richard B. Nye, who with his father and three Carinas won two races and almost a third, told me, “We used to swing for the fences a lot.” Jim McCurdy designed two Carinas and sailed with the Nyes, as did his daughters, Hope and Sheila. They learned the lesson well: don’t be afraid to take a chance.

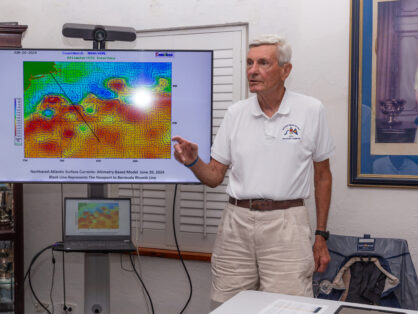

On the night before the start, Sheila spread out a multi-hued satellite image of the race course, pointed to a big circular eddy north of the Gulf Stream, and said, with her characteristic decisiveness, “We’re going there.” There was a waypoint 50 miles west of the rhumb line and placed near the top of a big clockwise-swirling circular eddy. In the southwesterly wind that was forecast, getting there meant sailing close-hauled, hard on the wind, for more than 100 miles.

Did we do it? The short answer is yes. After we reached Bermuda, while wandering the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club piers looking at boats and picking up chitchat about the race, I overheard someone say this: “It’s not hard to win a Bermuda Race. Get a good start, sail west, then collect your trophy.” I wish it were that easy, but that’s not a bad outline.

We got the good start. Dave Brown (the other watch captain and Sheila’s husband) put Selkie on the line at the committee boat end at good speed. We tacked to port across the strong ebb current, and when we ran out of water, went back to starboard, established an angle of heel that would define our lives over the next four days, and with Sheila steering started to point and point and point. Squeezing off a Swan 43 on our starboard quarter gave us an open lane to the eddy and proved to me, a new jack in the crew, that this boat could do what was asked of her.

Peeking under the boom I spied the main competition, two boats that Selkie had been dueling for years. One was Edwin Gaynor’s Aage Nielsen-designed Emily, always at or near the top and now sailing her record sixteenth race to the Onion Patch. The other was Sinn Fein, Peter Rebovich’s Cal 40 and the most successful Bermuda Race boat in the first ten years of the 21st century—winner of her class in the last three races, and winner of the ORR rule division in 2006. Happily for us, Sinn Fein was sagging off. “She can’t climb up there,” I recall thinking (and hoping), “which means she won’t make the eddy.” And so our true thrash to St. David’s Head was under way, with Selkie tight to the breeze.

The log records some excitement early on: “1825, whale and dolphins all around.”

The next morning: “0740, .5 knot current.” We were in the eddy, being swept south toward Bermuda.

“1300, flying fish and good current boost.”

“2000, still enjoying 2.7 knot boost.”

“0330, current down to .5 kt.”

Over those 20 hours of sailing with our sheets slightly eased, and with Selkie making 8 to 9 knots over the bottom, the apparent wind wavered from light to over 20 knots. Reefs went in and came out, the light and heavy genoas and the number 3 jib appeared and disappeared, the sea was dramatically disturbed, the decks became very damp, and not everybody who sampled Annie Becker’s tasty stew succeeded in holding it down.

We were seven, three women and four men. Annie and Carol Vernon—both extremely experienced offshore sailors—were on Dave’s watch, and I had Rush Hambleton and Morgan McCurdy, Sheila’s nephew. The captain stood many tricks at the helm and helped out with most sail changes, when she was not studying up on our next tactical decision, which was what to do when the eddy fed us into the Gulf Stream.

At 0930 Sunday we were in the Stream, and headed 20 degrees. We tacked to port to sail to the targeted eddy with a strong lee bow current. Here was our big gamble. Going to the eddy was an easy call. Would the southwesterly really fill in? It did. By noon the breeze began clocking into the southwest and soon it was over 25 knots apparent.

We had no idea what the others were doing because the sat phone and computer were at odds with each other. There was some frustration. Others wanted to track other boats, but I said, “So what? We can sail only one boat.” Knowing that Sinn Fein and Emily were out there somewhere was motivation enough.

We later learned that at this point we were leading the race with Sinn Fein many miles astern. Not as close-winded as Selkie, she had tacked up to the big eddy that we had fetched on one long starboard-tack leg. Kelly Robinson, their navigator, later told me in Bermuda: “We sailed a long time and worked hard to get into that eddy. It was hard to find it. We really had to battle to go into the ring.”

There was more than one battle going on. The crew, which has been sailing together for years, had a dissenter from the eddy strategy, “Why are we going west?” Peter Rebovich Jr., the tactician, kept asking. Bermuda was to the east. A retired school administrator who has been racing Finn Sein for decades, Peter Rebovich Sr. is not the sort of person to underestimate challenges. He knew who the competition was. Before the wet thrash killed off their electronics, he had caught a glimpse of us on the tracker on the Bermuda Race website. After the race Sheila asked him if he was worried about us. “You didn’t worry us—you were driving us crazy!”

They did go west, they did find the eddy, and when they left its southern boundary, Sinn Fein trailed Selkie by at least 30 miles, as much as four hours.

By then we were in the southwesterly and tacked onto starboard and were riding the front edge of this new breeze 300 miles to Bermuda on a nearly straight track. Sinn Fein caught that new breeze without having to probe for it. Slightly cracked off, she was at her best angle—a close reach, chasing and gaining on Selkie.

On that long sprint to the finish, the bond among our crew tightened. Within minutes of the command “sail change,” at least one member of the off-watch was climbing up the companionway to lend a hand and give Sheila a little rest. Once I tacked over to port for to help the foredeck guys get the number 4 jib set in 30 knots apparent and a quick seaway. This ended up taking nearly half an hour—a lot of time to give away when you sense the competition snapping at your heels—yet I’m convinced it was the correct decision given the weather and the crew’s weariness.

For a boat that doesn’t leak, Selkie was getting pretty damp below, what with all the goings and comings of wet sail bags and wet sailors, and the conversion of the forward cabin into a clothes hamper. I eased my laundry problem by wearing swim trunks and a T-shirt under my foul weather pants and jacket, but after a day or so I was feeling a little hypothermic. The most demanding job was putting on and taking off my shoes. Leaning down to tie the laces, I could have been reaching into the Grand Canyon. (“Yoga, yoga,” I kept telling myself. “You’ve got to do yoga.”)

Sleep came easily but, with all that adrenalin flowing, it did not last long, and real rest was hopeless. At night, the numbers on the instruments were fuzzy with my tiredness, so I turned steering over to my watch mates and they did handsomely—young Morgan getting the hang of it. I recalled how his grandfather, in his reticent manner, had guided me 40 years earlier. My style was more effusive. When I encouraged them by offering the promise of the rum drink of their choice—“will it be Planter’s Punch, boys? Or a Dark and Stormy?”—Rush drew his finger across his throat in the classic “cut” signal. Rush fought seasickness and exhaustion so dutifully that he once looked up and me and said, “I’m letting you down, John.” No, he wasn’t.

A day later we were a few hours off Bermuda, Rush was wolfing down Annie’s shepherd’s pie, 45-footers were all around us, and there were reports on the VHF of very recent finishes of 50- and even 60-footers. When North Rock appeared ahead, Sheila took the helm and we beat to the finish in air wafting eau de oleander down to us from Bermuda’s shore. We heard Ed Gaynor in Emily checking in almost an hour astern. We had her beaten.

But what of Sinn Fein? Sails down, powering though the night to Hamilton in exhausted near-silence, we heard Sinn Fein finish two hours behind us. We needed more than three. She beat us on corrected time by 1 hour, 4 minutes—less than 1 percent of our elapsed time. Peter Rebovich, that fine man, had joined Carleton Mitchell in the small pantheon of skippers who have won consecutive Bermuda Races. Besides the St. David’s Lighthouse Trophy, Sinn Fein also won the new North Rock Beacon Trophy as top boat under IRC, beating us by 25 minutes.

Another second place for Sheila McCurdy and Selkie—and for John Rousmaniere. There was a slight disappointment, but greater honor.

Latest Bermuda Race News

July 9, 2024

The Loss of Solution on Return Delivery

On July 2nd, during the return delivery from the 2024 Newport Bermuda Race, the crew of Solution abandoned their 50-foot sloop, 200 miles south of Cape Cod, and were safely […]

June 29, 2024

Race Wrap Up – Historic 53rd Newport Bermuda Race Concludes with Prize-Giving

Final winners and awards announced on Saturday Photo: Steve Cloutier [Hamilton, Bermuda] - The 53rd Newport Bermuda Race officially came to a close this evening, as winners and award recipients […]

June 27, 2024

Navigators’ Forum Recap: Expert Insights and Winning Strategies

The 2024 Navigator's Forum